Americans don’t know it yet, but we’re sitting on the beach awaiting a tsunami. Not a literal tsunami but a giant wave of problems with our healthcare, all stemming from the Backsliding Boondoggle Bill (BBB) signed by POTUS at a July 4 White House ceremony.

When will this tsunami hit? Most of the Medicaid cuts in the BBB will affect Americans after the 2026 midterms. If the Democrats take back the House and Senate, as some predict, who will get the blame for the dearth of coverage?

I heard Senator Charles Schumer is writing a strongly worded letter, while millions brace for impact.

In March 2025, approximately 78.6 million Americans were enrolled in Medicaid programs, split between Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Medicaid was born out of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs, specifically the Social Security Act of 1965. Medicare was established with the same LBJ signature and funded hospital and physician services for persons sixty-five and older, with coverage added two years later for individuals with disabilities.

My state, Indiana, did not have Medicaid services until 1970. My paternal grandmother spent the last three years of her life in a facility in Logansport, Indiana, which stank of urine. Her children sold her home and many of her goods, and she spent her money on the facility so she could qualify for Medicaid. In those days, facilities typically had only one double room for women and one for men.

At my grandmother’s facility, her double room was at the end of a long hall, and a cardboard sign indicated on the door, “Female Medicaid Beds.” I never got that indignity—she was referred to as a “bed,” not a patient.

In 1973, Medicaid came with shame and stigma.

Today, one in four Americans and nearly half of all children rely on Medicaid or CHIP. The stigma is gone, given the significant need and expense. In 2023, 100 million Americans benefited from the Medicaid and CHIP programs.

The BBB will directly impact people who currently receive Medicaid and CHIP services (between 2026 and 2034). These effects include:

Work requirements: The new legislation mandates that most adults aged 19 to 64 will be required to work 80 hours per month to maintain coverage.

Doubling of eligibility checks: Eligibility checks will now be conducted twice a year instead of annually, potentially increasing the likelihood of coverage loss due to paperwork errors.

Increased co-payments: Individuals with incomes above the poverty line may be required to pay up to $35 for a doctor’s visit co-payment. (In my state of Indiana, for a family of four, that’s around $44,000) Some may defer preventative care.

What most Americans, especially those with commercial health insurance or Medicare, fail to realize is that the tsunami is coming for all of us.

I spent 35 years of my career working on the business side of healthcare, and I’ve watched us transition from a Fee-for-Service model to Prospective Payment to the current situation.

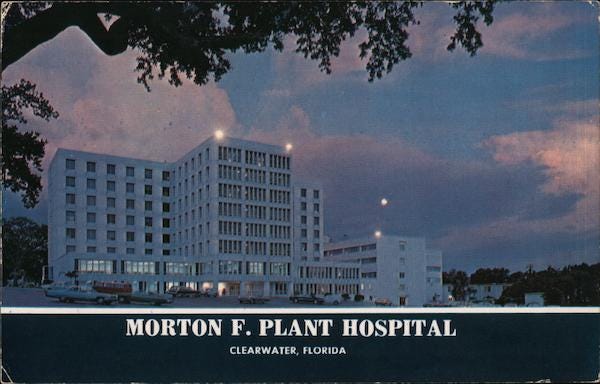

My first day working in a hospital was on August 1, 1982, at the 800-plus-bed facility of Morton F. Plant Hospital in Clearwater, Florida. This large non-teaching hospital was often full. The population of Pinellas County, located on the Gulf of Mexico, swelled during the winter months with Snowbirds from Canada and the northern United States.

Because Medicare just paid the bill, it wasn’t unusual for older adults — especially those with family far away — to have long hospital stays to recover from the illness that put them there.

In 1983, Medicare began reimbursing hospitals on a diagnosis-based, predicted outcome basis, using all its available data. I know I’m in the weeds here, but stick with me. Medicaid found prospective payment to be a reliable indicator, superior to the fee-for-service reimbursement, and moved in that direction. Like that first initial wave on the beach, prospective payment changed American healthcare forever.

Prospective payment gave rise to a new industry: outpatient everything. Before the early 1980s, there were few outpatient clinics. After the implementation of prospective payment, surgeries that were previously performed in hospital surgical suites were moved to free-standing surgery centers, which maximized revenue for hospitals. The for-profit hospital chains grew.

Today, America’s healthcare costs are extremely high and continue to rise. American healthcare costs totaled $4.9 trillion in 2023, representing a more than 7% increase over the prior year. In 1980, CMS reported that the cost was $247. Even this left-brained writer knows that 4.9 trillion is bigger than 247 billion.

What’s the bottom line?

There are significantly wider impacts for our healthcare system due to the dismantling of Medicaid by the BBB.

Bye-bye Rural Hospitals: I worked in a rural hospital that eliminated its obstetrics and gynecology department thirty years ago. There have been many healthcare deserts since the introduction of prospective payments. With a heavy reliance on Medicaid, rural hospitals are facing a rising tide that is growing higher above them, which I don’t particularly consider rural. For example, on a list of potential closures is Baptist Hospital, Madisonville, KY.

Madisonville, KY is a town of about 20,000 people, and guess who its largest employer is? If you said Baptist Health, you win the prize, a trip to the unemployment line.

Many of the hospitals on the rural hospital list are the largest employers in these towns. And they provide jobs and healthcare to a wider area, including tiny towns and villages 75 miles in any direction. Good-paying jobs with benefits from these hospitals will disappear, leaving their communities economically underwater.

What’s Left is Going to be Busy: As hospitals close and patients lose coverage, hospital emergency rooms — often busy during flu and cold season—will be busier for everyone who needs emergency care. What has always happened with surges of uncompensated care is that hospitals shift the cost to paying patients, a practice known as “cost-shifting.” So, everybody gets less timely care, thanks to the BBB, with the benefit of it costing more.

Stress on the Existing Healthcare Workforce: If there’s even a group of workers who have experienced stress, it’s those who provide our care. Healthcare providers are not perfect, like us; they are human. However, most healthcare workers had to report during COVID and didn’t get the holidays off that other types of workers do. And there’s an elevated level of burnout. The BBB isn’t going to ease the lives of health providers.

So that’s where we are, on a beach with a large wave cresting ahead. I cannot offer suggestions on how to stop the wave. I don’t even know how to run for cover, myself, a person covered by traditional Medicare. Put your waders on because it’s going to get deep.

-30-

Read more about it:

Potential Hospital Closures in Indiana and Kentucky

State of Indiana Medicaid Guidelines, 2025

1980 healthcare costs from CMS

Our congressional representatives couldn’t wait to sell us down the river.

Amy, what an informative article everyone needs to read. Thanks.